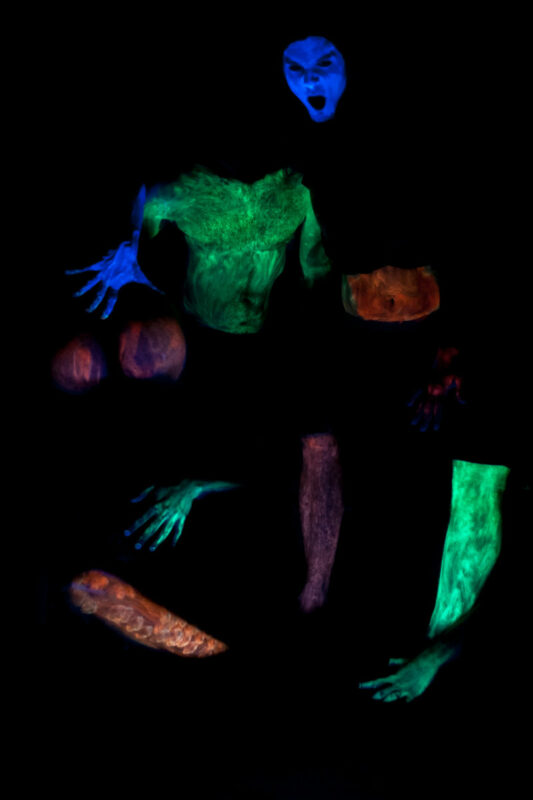

Gio Montez presents the performative collective Barbari Sognanti, led by Vitaldo Conte. Positioned between ritual, performance, and documentation, the action transformed a dense, ecstatic performative environment into a field of visual and conceptual experimentation.

Through a dynamic scenic direction and an experimental audiovisual practice—centered on the inhabitable installation known as “the cage”—Montez explored the threshold between self and other, documentation and creation. Video and photography became imaginal devices, deforming reality to generate poetic content. The resulting works—a video and six unique photographs—render the performative bodies as an immaterial presence, a “cloud of smoke enclosed in a cage,” existing only through its relational context.